Pat Dorsey on competitive advantage

How I invest part 2: Investment moats and where to find them.

If you’re new to the “How I invest series” this is Part 2. I’m writing this to document the mental models I have gained from 3 videos that were more valuable than my entire university economics education was for equity investing.

Part 1: Competition is for Losers with Peter Thiel

Part 2: The Little Book that Builds Wealth with Pat Dorsey

Part 3: The philosophy of Fundsmith

Disclaimer

In no event will Prdctnomics or any of the Prdctnomics parties be liable to you, whether in contract or tort, for any direct, special, indirect, consequential or incidental damages or any other damages of any kind even if Prdctnomics or any other such party has been advised of the possibility thereof.

The writer’s opinions are their own and do not constitute financial advice in any way whatsoever. Nothing published by Prdctnomics constitutes an investment recommendation, nor should any data or Content published by Prdctnomics be relied upon for any investment activities.

Prdctnomics strongly recommends that you perform your own independent research and/or speak with a qualified investment professional before making any financial decisions.

Here we will take a deep dive into the concept of competitive advantage or an economic “moat” from Pat Dorsey.

Pat Dorsey on Moats

Put simply capitalism works: capital seeks the highest returns possible.

If a company is making a lot of money other companies will immediately seek to compete with it

High profits attract competition as surely as night follows day. Competition eventually destroys profits.

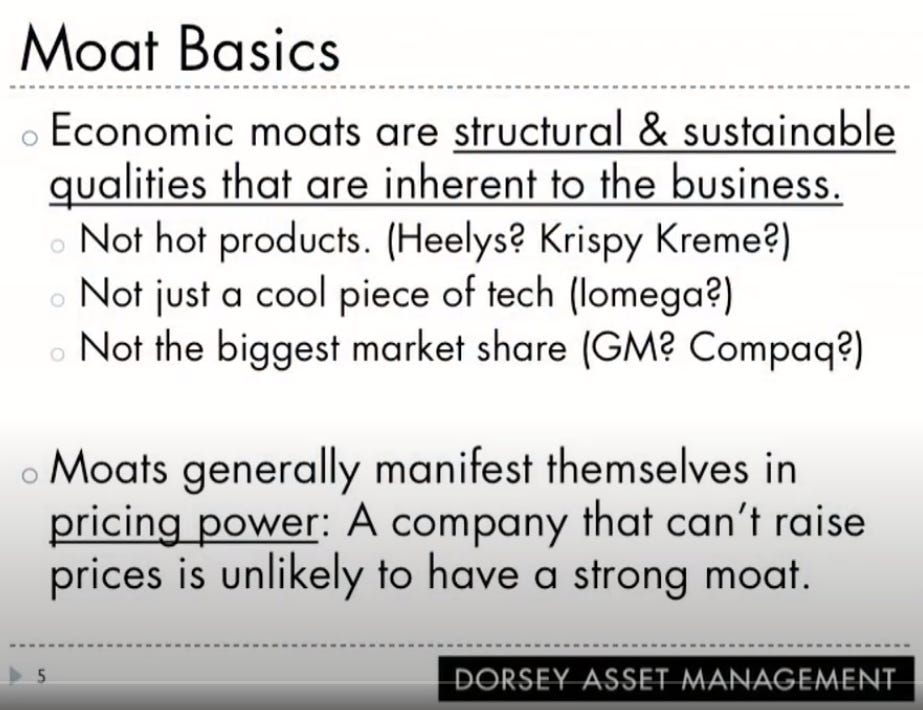

If you look at the highest cohort of companies by profitability today and check again in 10 years most will have lower returns on capital due to competition. There are a minority of businesses where that is not the case. These purported structural advantages Pat Dorsey calls moats.

This allows businesses to make large profits over a longer period of time than academic theory would suggest.

What are the types of moats?

A moat is not a hot product. At one point Heelys was an 800 million dollar market cap company.

When companies cease to raise prices on a regular basis it is usually a sign they are losing pricing power. This could imply there is a viable competitor, or there is some event going on causing them to lose their market position. These are usually the first signs their moat is eroding.

Pat looked for companies that made well in excess their costs of capital for long periods of time.

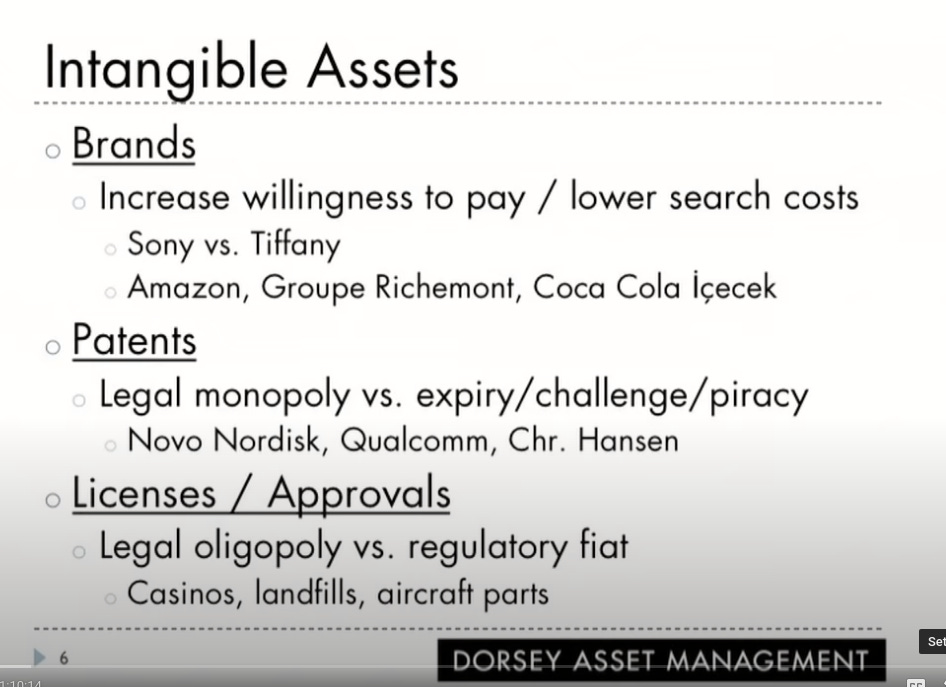

Tiffany will charge 20% more than competitors for the exact same diamond, but the perception of the Tiffany product makes the decision worth it for people. Example: “will probably get a bigger smile from the recipient if it is in that Tiffany box, vs not in that Tiffany box, so they can charge.”

Low cost brands that lower search costs by being well known let people make quick choices to buy especially when the absolute price difference isn’t that big (name brand Ketchup, Coca-Cola). It is however not enough for a brand to lower search costs if it does not give the brand pricing power.

Patents are a legal monopoly on a product but they expire, can be challenged, or ignored. They are much more valuable as a portfolio of many patents vs an individual blockbuster patent. If a company has only one valuable patent the incentive to challenge is high, but if a company has many patents applying to their business the incentive to challenge declines.

Licenses and approvals can be a moat. It is hard to start a new casino, people don’t like living next to landfills or gravel pits, etc. FAA approvals for airline parts are hard to get, most aftermarket parts are single source so they often get 40% margins.

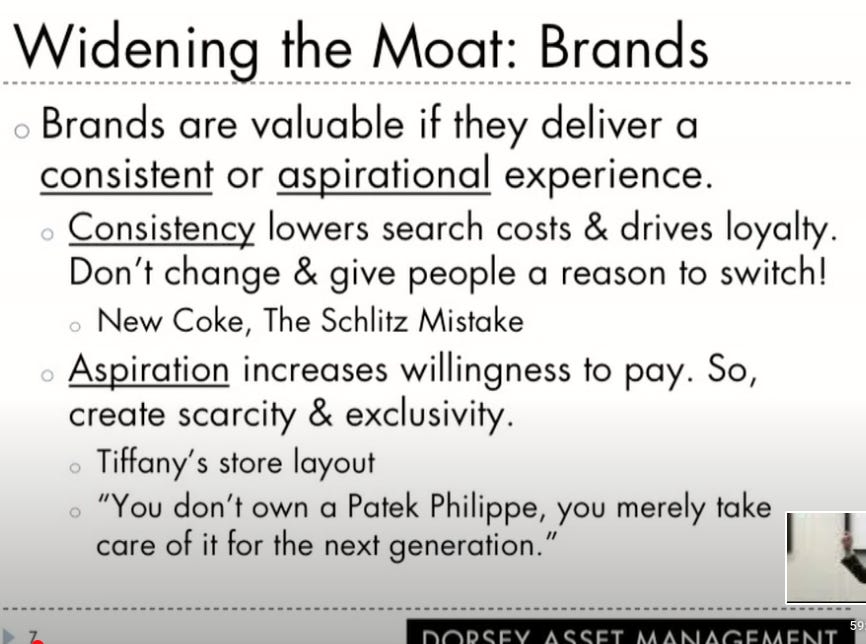

Brands are valuable when they deliver a consistent or aspirational experience. This means if the product is selling well you don’t change the damn product!

Schlitz used to be the second highest volume selling beer in the US. They changed the flavor of Schlitz and they never recovered their market share. If people are buying why change it?

Tiffany gets over 40% of their revenue from items that sell for under $200. One of the ways they maintain the high end nature of their brand is by putting the most expensive items in the front of the store, it maintains an aura of exclusivity and scarcity. Upon walking to the back of the store the prices are lower and your mind has anchored to the higher prices.

Aspirations differ by culture and area, so you want to find companies that can adapt. For example Jack Daniels emphasizes an old school cowboy branding in Russia, but has developed a more urban / youthful persona in China.

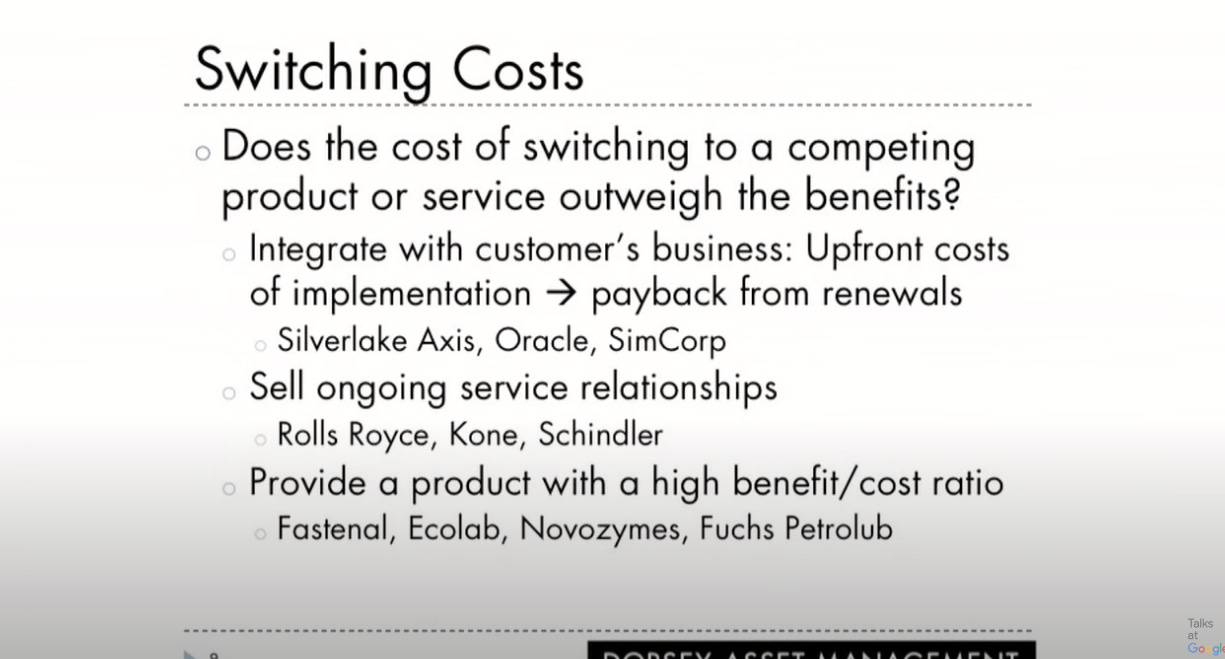

Switching costs can provide a moat if the company deeply integrates with their customers.

Service contract attachments can also be a moat, for example in the elevator business. Rolls Royce sells their jet engines via “Power by the hour”.

Another switching cost advantage is having a very high benefit to cost ratio. For example a high quality lubricant that can increase the uptime of a giant mining machine, even if that lubricant costs 20% more than the next highest cost lubricant it is such a low cost input relative to the labor, machinery, and cost of downtime that the customer will happily pay a premium.

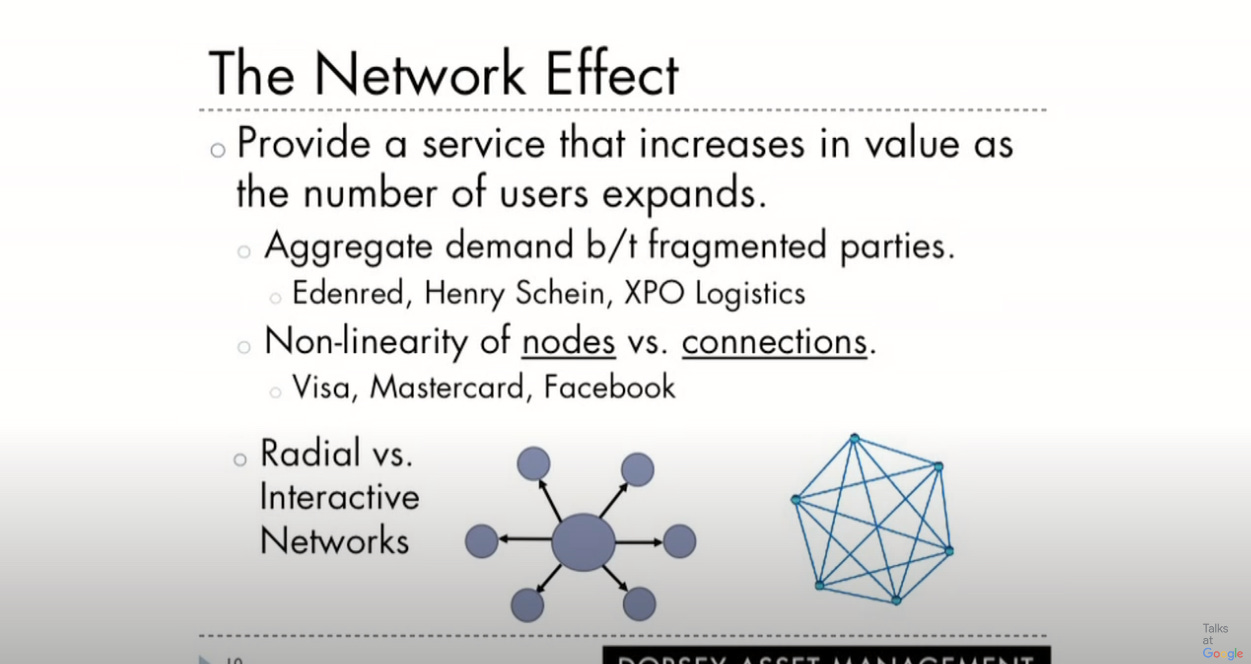

Network effects are fairly famous in Silicon Valley. A product with network effects is any product where the value of using the product increases with additional users. Examples include a social network, telephone service, a payment processing network, or a messaging app. Another example is connecting fragmented buyers and sellers. Henry Schein aggregates fragmented demand and fragmented supply and this allows them to charge more in the dental business.

Beware of radial vs interactive networks. Radial networks are much less valuable. Example of a radial network vs interactive network is Western Union vs VISA. Western union is a series of spokes or channels and doesn’t become more valuable with more users in a non-linear way.

Some examples of process advantages were companies that “near shored” their fashion product manufacturing to respond faster to changes in consumer tastes. The issue with process improvements to a moat is they tend to be short lived, competitors will learn of them and replicate them as best practices.

Scale tends to be a much more robust advantage. DHL lost over 1 billion trying to compete with UPS and FedEx in the USA despite being a very well run business because they never could reach the established scale of the existing package delivery firms in the US.

Niches can also lead to enormous profits. Many niches are not large enough to support many players and also have limits to growth that make them unattractive to new entrants, but as an incumbent they can be enormously profitable subject to those limitations.

Does management make a big difference?

Usually not, Pat gives the example of a great Jockey on a goat, vs him on a horse. He will probably beat the goat.

The quality of management needed to succeed is inversely related to how good of a business is. Moats can protect management from their own mistakes. Airlines will never have lower costs than the day they open for business, no matter how great their management they tend to destroy capital. Planes wear down, employees gain seniority with higher pay, etc.

Good managers can still make great businesses better. Amazon is always looking for ways to improve the customer experience which has no cap on how good it can become. Costco is always looking for ways to scale and offer lower prices or higher quality products to their customers. Those cost savings lead to more customers which leads to more scale which leads to lower prices in a virtuous cycle.

Bad managers enter businesses they don’t understand lowering returns on invested capital. One example is Cisco entering the consumer business. Garmin had great franchises in avionics, as well as vehicle GPS then tried to enter the handset market for cell phones out of fear of GPS becoming a feature of phones, which it did.

A key point to note here is if companies are diversifying because because their core businesses are dying they are more likely to destroy capital making irrational and desperate choices along the way. Alternatively if they are diversifying out of strength where their core businesses are already thriving they are more likely to be making rational choices on what businesses to enter next.

There are rare examples of operators who start in poor businesses and still manage to become extremely successful. In Q&A Deloitte did a study on the “3 rules” of what successful businesses did where returns do not reverse to mean. You can read about that here. The gist of the study is rule 1: don’t compete on price, compete on value. Rule 2: revenue before costs. Don’t cut costs while there are still opportunities to obtain higher prices or higher volumes.

During the Q&A traditional value investing was also discussed. Time is the friend of a good business, but not that of a bad business.

Local factors can create moats for businesses that wouldn’t exist elsewhere. For example car washing businesses in Germany are uniquely advantaged because there are regulations on where car owners can wash their cars in Germany. There are also more opportunities for minimum efficient scale (Thai language media).

Flavors for candy generally are not popular outside of their home country so local candy firms often have moats, while the same is not true for beer which does travel.

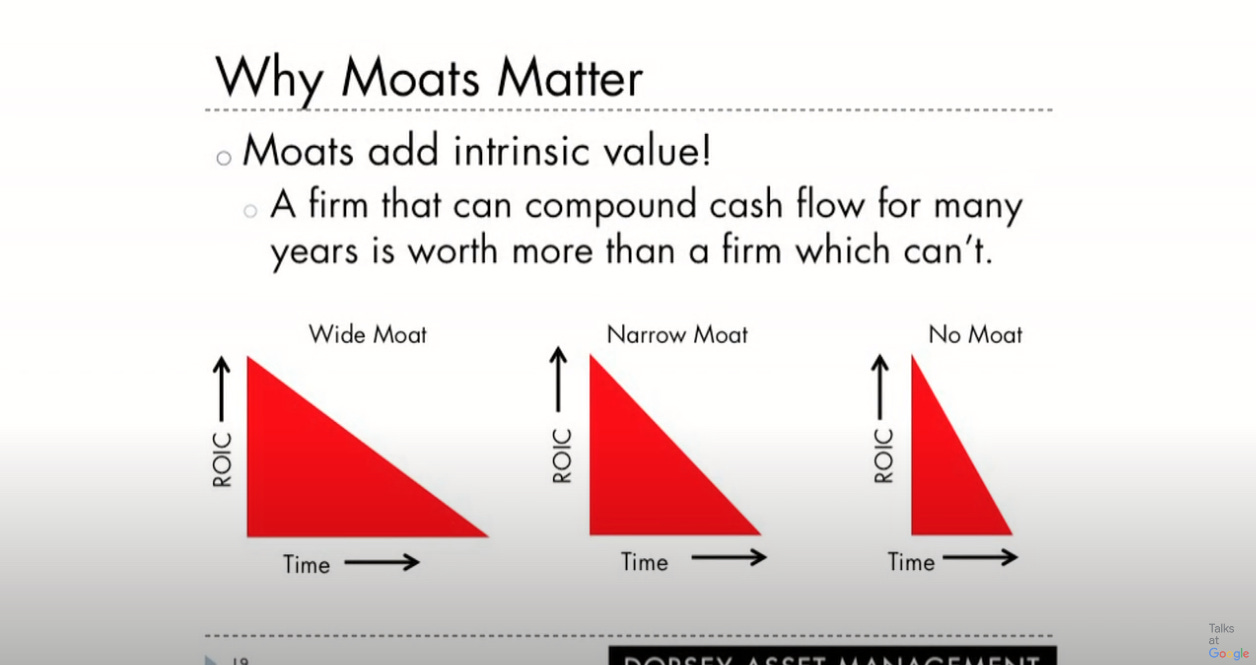

Why do moats matter?

These slides go together well, a moat without the ability to reinvest adds to certainty (possible outcomes are limited) but should be valued lower than a business with a moat and reinvestment opportunities. The example he uses is McCormick, consumption of spices just isn’t going to grow that much. He states it is a business you wouldn’t want to pay 30 times earnings for. It currently trades for 32.5 at the time of this writing. He also lists Microsoft and Oracle as companies without many reinvestment opportunities which may have been true in 2015.

Moaty businesses are not limited to the “Warren Buffet” type companies. Even if slow growth stable companies can pay out a lot of their free cash flow there are more desirable businesses that can reinvest those profits at a high sustained rate and those are “totally awesome”.

Real world example: Motorola. Motorola from the time it released the RAZR to its peak had 22% market share, but there was no lock in. People over estimated the moat Motorola had and lost substantially if they were investing as if the success of the RAZR was going to continue.

As an illustration of the opposite problem Buffet mentions he was buying into Wal-Mart stock but it started to move up in price and they decided to wait for better prices. The opportunity cost of this ended up being 8 billion dollars to Berkshire.

Most investors spend time on margin of safety and not on opportunity cost.

Isn’t the moat priced in?

Sometimes it is priced in, Cisco trading at over 100+ P/E in 1999 being one example, but most investors have a very short time frame. The average turnover of a US mutual fund is 100%, and most investors focus on short term changes in price and not long term changes in moat.

“All of the information is in the past, but all of the value is in the future”.

Pat Dorsey believes that quantitative data is efficiently priced into securities and picked over by funds, but qualitative data where an investor must work to understand the factors that lead to moats is less examined.

When looking to model high growth companies it is helpful to think in fixed vs variable costs, and consider what marginal costs to generate marginal revenue a company will have as it scales.

If you liked this and would like to see more similar content please subscribe, share, and like.