How I approach investing

Learning from some of the best minds in business (Part 1 of 3)

Disclaimer

In no event will Prdctnomics or any of the Prdctnomics parties be liable to you, whether in contract or tort, for any direct, special, indirect, consequential or incidental damages or any other damages of any kind even if Prdctnomics or any other such party has been advised of the possibility thereof.

The writer’s opinions are their own and do not constitute financial advice in any way whatsoever. Nothing published by Prdctnomics constitutes an investment recommendation, nor should any data or Content published by Prdctnomics be relied upon for any investment activities.

Prdctnomics strongly recommends that you perform your own independent research and/or speak with a qualified investment professional before making any financial decisions.

How I approach investing

Nothing has been more harmful to my investing performance than the combination of the efficient market hypothesis and the concept of investing based on price to earnings or price to book multiples.

It is pretty easy to see why. It seems very different business models actually deserve very different valuations. While I didn’t do poorly by being in index funds and ETFs I missed out on some obvious trends because it didn’t fit into my mental models. One of the most destructive was the tendency to avoid companies due to price to earnings multiples. These valuation mental models are heavily skewed towards a time when public businesses were largely homogeneous and lacked competitive advantages. When factories adopted new processes and technologies others quickly did the same. Excess profits were quickly competed away so the best way to ensure profits when investing as I understand it was to buy into companies as far below their net asset value as possible. That isn’t to say classic value concepts are broken (although they are certainly out of style right now), but these new models of thinking appear to be working much better for me right now. Could it be short lived? Could we be in a bubble in quality and growth? Certainly. It wouldn’t be the first time either. However I seem to have both more resolve and success with these lines of thinking than my attempts at value and factor investing.

Over time I find myself revisiting these concepts and applying these mental models again and again. With these reality filters once you see it, you can’t unsee it.

What are my new mental models?

Investing in value and struggling businesses is a bit like buying a melting ice cube for less than its currently worth, while investing in quality and growth assets is like investing in a snowball rolling down a hill. Both approaches have merit, unique and differing risks, and likely require different temperaments to be successful.

When looking at the above before even thinking about valuation one must think about what makes a good company. What are the best companies? How does one distinguish between mediocre and great? It turns out very few meet the bar. Many snow balls and hills may turn out to smaller than we expected, or worse end up being melting ice cubes.

When looking for the biggest compounders of capital one must first eliminate most companies which don’t compound their capital at rates higher than their cost of capital. To understand the prerequisite circumstances for when this happens I’ve learned from several people who have had immense success as entrepreneurs and investors in these types of businesses and somehow found the time to share their knowledge with us plebeians.

To share these mental models I will first walk you through 3 videos that are more valuable than my entire university economics education was regarding equity investing. While I also cover, summarize, and elaborate on the contents of the videos I do recommend watching each.

We will start with Peter Thiel, entrepreneur, investor, and author of Zero to One.

Competition is for Losers with Peter Thiel (How to Start a Startup 2014: 5)

Riches in Niches

It is much better to own and then grow with a niche than to try to enter a large existing market. It is always better to be the biggest fish in a small pond.

Start small and monopolize, it is easier to dominate a small market than a large one. If you think your initial market is too big, it is.

Almost all monopolists in Silicon Valley started with a small market and then expanded into adjacent markets.

Amazon started with books and moved up the value chain to general e-commerce, and now every imaginable physical and digital good, cloud services, etc.

Ebay started with collectible goods like beanie babies and expanded to all goods.

PayPal started with just eBay as their target market.

Facebook’s initial market was Harvard University.

Business schools typically discount the relevant initial markets for startups which appear so small that they have no value, but startups can build from these markets outward into ever larger markets.

If a company is starting with a massive market (all of energy for clean tech) presenting their potential market as hundreds of billions or trillions is a red flag. You want to be a one of a kind company in a small ecosystem, not the 10th thin solar panel company, or the 100th restaurant in Palo Alto.

As a business it's good to go after markets that seem so small they don’t make sense then scale from domination in that small market outward.

The history of technology is such that each great opportunity happens only once, the next Bill Gates won’t start an operating system company, the next Mark Zuckerberg won’t start a social media company.

All unhappy companies are alike: they failed to escape the plague of competition.

If iterating on an existing concept your product must be an order of magnitude better than the existing product or it will be hard to convince people to adopt it.

This is not the monopoly you’re looking for.

Monopolists pretend to have competitors, while non-monopolies pretend not to.

Non-monopolies will try to emphasize their competitive advantage often when none exists, for example presenting their restaurant as the only British restaurant in San Francisco, which isn’t actually a monopoly as any restaurant is a substitute.

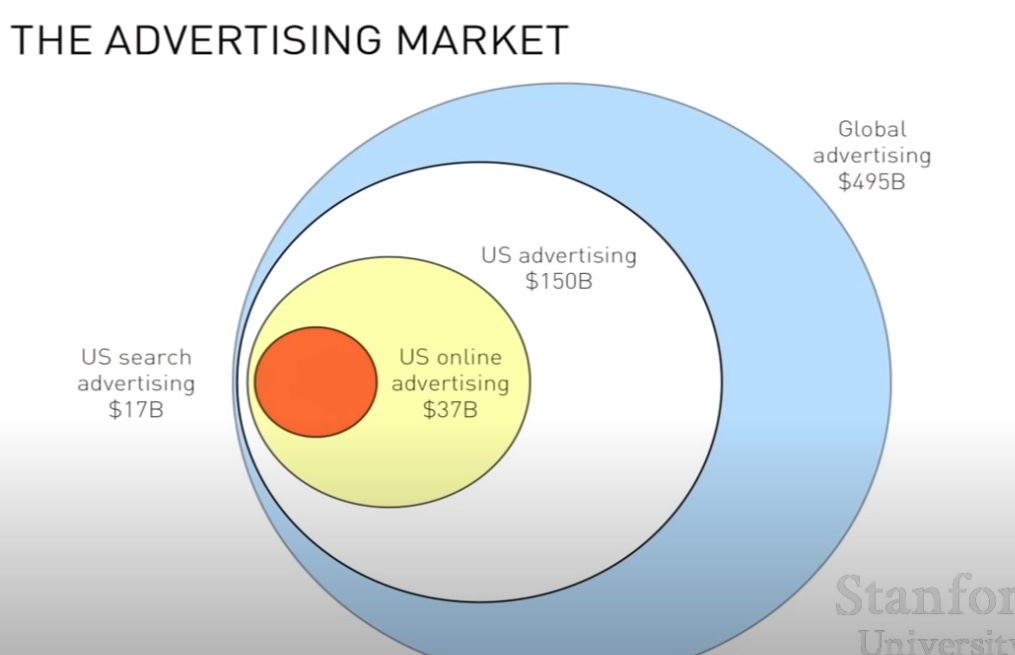

True monopolies will emphasize their revenue streams are a small total percentage of many combined markets, like all of advertising not just search or digital advertising. Amazon has broken out its market share in the US as a percentage of commerce, not a percentage of e-commerce when discussing with regulators.

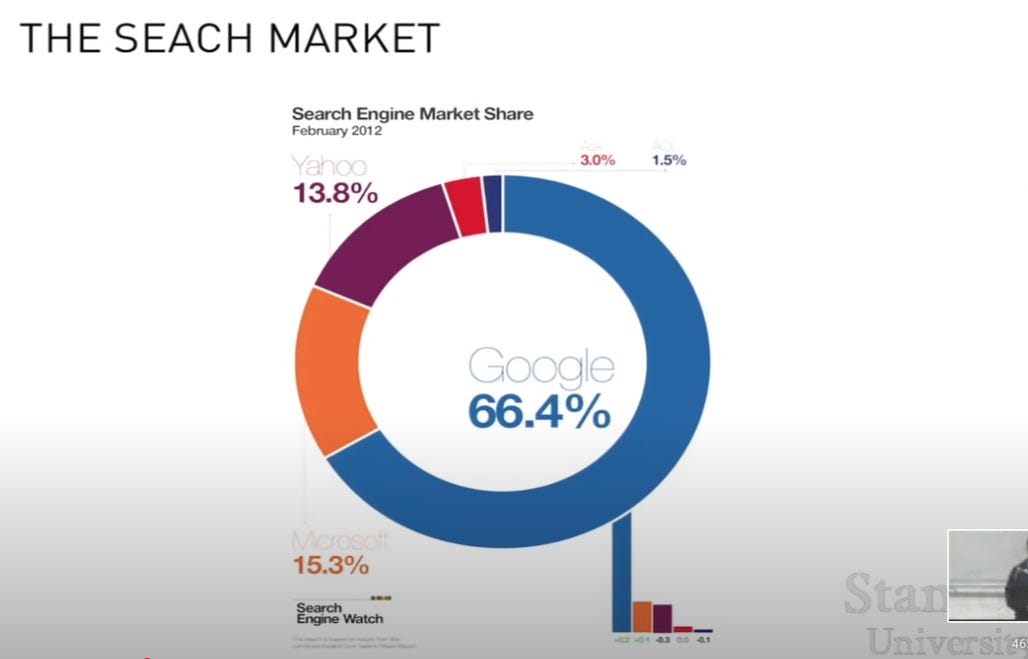

This example with Google is particularly interesting as America re-examines antitrust actions against big tech. Google owns almost the entire search market and has purchased many digital advertising giants outside of search over time, so the below is very out dated.

However Google presents itself as an advertising company, or technology company, not a search company with the goal of showing themselves as a small part of a significantly larger market. This creates the narrative Google is extremely small relative to the total market and therefore not a monopoly. Alphabets “other bets” may be an attempt to further obscure this monopoly power.

High gross margins and free cash flow, as well as cash build up on the balance sheet are indicative of potentially being a monopoly as they demonstrate pricing power.

What are attributes of a lasting monopoly?

While hard to get started a monopoly can form due to network effects (Facebook being the classic example). Network effects are exceedingly difficult to establish (why be the first person on a social network?), but even harder to disrupt.

Any business that has very high fixed costs and very low marginal costs tends towards monopolies. ISPs / Cable, Cell Carriers, etc.

While not examined in depth here monopolies based on brands alone are possible.

Software by virtue of having no or very low marginal costs can easily scale with demand should it arise.

These companies, if they can continue their growth, have most of their potential value far in the future. However Silicon Valley has a tendency to over focus on immediate growth, and under focus on durability.

Even proprietary technology is tricky, and it alone is insufficient to be a durable competitive advantage. There are many cases where there was a tremendous breakthrough in technology which was then leapfrogged. This innovation is excellent for society but not for your business. By definition it is ideal to be the last mover not the first.

An example industry that underwent this was the disk drive industry where many companies had the best disk drive technology for a short duration of time. Clayton Christensen explores this more in depth in The Innovators Dilemma. These incremental innovations in disk drives never quite reached the escape velocity needed to avoid future competition.

The question must be asked which companies are likely to still be the leader 10+ years later in their niche.

History of innovation

Thiel goes on to describe great innovations that created tremendous value for society but the inventing party didn’t capture any value from their invention. Businesses often create significantly more value than they capture, and its actually rare that inventors capture more than ~0% of the value created from their invention.

Examples of this are early textile factories. The competition structure prevented both the capitalists and the laborers from capturing the value of their innovations. The revolution in textile manufacturing and steam mills did not really add new names to the land owing aristocracy in Great Britain, Albert Einstein did not get rich from his breakthroughs in physics, and the Wright Brothers while ending up well off never reached the same level of wealth as later monopolists.

Vertically integrated monopolies when successful are immensely powerful, but take a long time to build and are often complex. Henry Ford and Ford Motors is one such example, Standard Oil another, and SpaceX has the potential of becoming a modern example.

Software itself seems to lend itself to monopoly more often than the world of atoms. This might be due to low marginal costs, economies of scale, and fast adoption which allows the company to scale quick enough to evade robust competition.

The microeconomics and structure of industries matters a tremendous amount. Markets with bad microeconomics are often later rationalized away by the parties in such industries. For example the idea that a good scientist doesn’t want to make money is one such rationalization.

Psychology of Competition

Thiel suggests we often think of “losers” as those who can’t compete, but in reality we should revalue this as competition itself being the issue. The draw to competition could partially be a psychological attraction to the struggle of competing, imitative or herdlike thinking, and / or as a form of validation. When one’s peers are working up the same ladder it is hard not to desire the same.

20k people a year move to L.A. to become movie stars, maybe 20 make it. Intensity of competition increases in elite schools, and managerial class jobs. The difficulty in differentiating yourself from others leads to greater and greater competition over smaller and smaller stakes.

Thiel discusses leaving an elite law firm where everyone outside wanted to get in, and everyone inside wanted to get out.

Competition of course makes you better at whatever it is you are competing in, but it often comes at the price of asking bigger questions about what is truly valuable.

Lessons

“Don't always go through the tiny little doors that everyone tries to rush through, maybe go around the corner, and go through the vast gate no one is taking.”

The above has a lot of implications not just for investing but also choosing where to work, what to work on, and avoiding group think. Peter Thiel is famous not only for his intellect but also for when he chooses to be a contrarian. No doubt walking away from the prestigious and high income legal career track he was on was challenging and must have seemed insane to most. It was also absolutely essential to getting to where he is today.

People and businesses that do something completely new have a luxury: no one else is doing what they do so they have no competition. If entering a crowded field to stand out one must be significantly better, an order of magnitude better. Truly great businesses have the magic combination of few likely competitors due to their competitive advantages, and a long runway of growth ahead of them. This means most of the companies’ potential value is in the distant future.

Short term thinking, recency bias, and anchoring have historically made me reluctant to bet on winners. After all they were cheaper not long ago, and their price to free cash flow might be unjustifiable with this and even next quarter’s earnings. However assuming I am right about a company’s market position and growth potential then my time horizon and the ability to hold long term is a competitive advantage.

Part 2

In part two I will walk though the ideas of Pat Dorsey.