Disruptive Innovation

Breaking down one of the most overused terms in tech

The following draws heavily on the Innovator’s Dilemma by the brilliant Clayton Christensen and will try to clarify what disruptive innovation actually is, what pattern it follows, and implications for product development and investing.

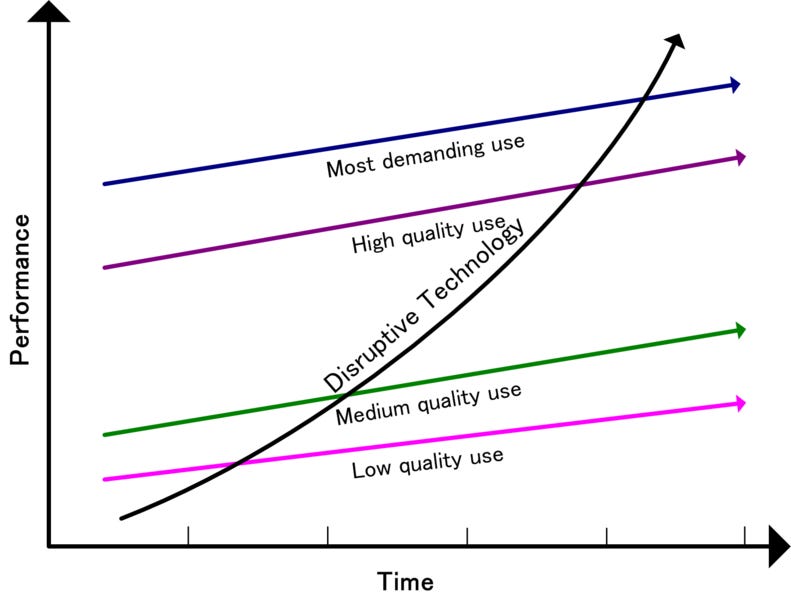

What patterns does technological disruption usually follow? Disruption is a heavily misused and overloaded term today. Typically true technology disruption starts on the low end of the market, follows an S curve of utility as sustaining improvements are made to the initial innovation, and those improvements allow the disruptor to move up market thus disrupting incumbents.

Source: Wikipedia commons

The innovator's dilemma is thus: When managing a business do you invest in cost reductions / process improvements (efficiency innovations), improvements to your current products as driven by data and customer asks (sustaining innovations), or do you invest in new technology that while inferior today has the potential to eventually displace your current products? The final one has the most risk, longest payoff time, and is likely to cannibalize your current highly profitable products in the process.

The final one is called disruptive innovation. Disruptive products are usually significantly less expensive than alternatives or create a new market that has no alternatives. The initial disruptive tech may seem impractical, niche, or a “toy” use case compared to existing tech, but successfully addresses a use case that is not attractive to incumbents.

At the start of the process the innovation may seem lacking significant utility, but as it improves and finds product market fit, more impactful improvements can be identified. Due to the economies of starting on the low end of the market, existing adjacent markets often look attractive to enter to the disruptive firm, whilst it will be rational to the incumbent firm’s management to retreat to the remaining high margin business areas they have available to them. This allows the disrupting firm to move “up market” into areas owned by incumbent firms often with less resistance than one would expect.

One example in the book is Honda Motorcycles. Honda wanted to expand outside of Japan and compete with Harley Davidson and BMW in the USA. Honda’s smaller simpler bikes were not competitive on features, or quality vs the US road bike market which was substantially different than the urban bike market of Japan.

The USA Honda team stumbled upon the use case of off-roading with the bikes themselves which the cheaper and smaller motorcycles excelled at. The Honda dealer network rejected the small Honda Super Cub precisely because they were listening to customers who wanted bigger, more feature-rich road bikes. Listening to customers is essential to producing sustaining innovations, but interviewing existing prospective customers outside of the right niche for disruptive innovations is likely to lead a product team astray.

Honda pivoted to a different significantly smaller distribution channel: Sporting Good Stores. As is typical in disruptive innovations, established producers do not see value in the innovative technology as they don’t actually know how the tech will be used or which features of it will be valued, and their customer base often has no use case for the innovation. Success hinges entirely on the innovating firm finding a market that values the innovation. This market often differs from the market the firm set out to enter and typically has a much smaller TAM.

As the newly created off-road motorbike market took off Honda and other Japanese bike firms captured most of the market share, whilst incumbent firms (in this case Harley Davidson) were not incentivized to enter the niche market. Initial use cases for the disruptive tech are often of no interest to market leader firms’ existing customers, are lower margin businesses, and as a market for an inferior good present a brand risk to incumbent firms.

The success of marketing a disruptive technology to a new market provides funds for sustaining innovations making the disruptive tech better each subsequent iteration. Eventually the disruptive technology becomes competitive with incumbent firms’ products, which usually have the added benefit to the disruptor of being higher margin products. This allows the disruptor to cross the moats of existing market leaders forcing them to retreat further up market themselves driven by their own customers asks and perceived needs.

If this pattern continues unchecked, the incumbent firm risks being replaced by the disruptor. Some firms will incubate disruptive technology themselves to fend off lower market disruption. Intel famously went down market with the Celeron processor to fend off low-end rivals like AMD after Andy Grove, then CEO of Intel, read Christensen’s book.

Disruption is a perpetual risk and many business moats are short lived as a result, even businesses with excellent management teams. One such example of a company that successfully self-disrupted multiple times before failing to do so was Kodak. Kodak successfully shifted their business multiple times self-disrupting (for example from clear high quality black and white film, to at the time lower quality color film) before failing to see the threat of digital photography.

Driven by the demands of an existing customer base, a company will be incentivized to chase sustaining innovation after sustaining innovation which pleases customers and drives profits in the near term vs investing in a potential new markets that might not become as profitable for years if ever. Business risk aversion and taking the seemingly prudent data driven path can eventually prove fatal when competing with a true disruptor. Quarterly earnings reports also encourage short term thinking and efficiency innovations over long term capex in potentially disruptive innovations. Many public companies are locked into both cycles of pleasing investors and existing customers making them vulnerable to bottom up disruption.

This creates an interesting opportunity: by having a longer time horizon a small insightful group of people can compete with less agile giants. First by growing in niches that are rationally ignored by incumbents, and then by moving up market. This applies to both startups and intrapreneurs.

Is your employer investing in disruptive innovations? Are your investments vulnerable?

An understanding of disruption can help you make better choices in how you build, and understand how well run companies get blindsided by disruptors.

Enjoyed reading this! thank you